PERSONAL

3,079

Gacha Games, and Altruism

7 years ago

Games which aim to drain your wallet dry by relying on essentially the roll of a die aren't really the epitome of altruistic innovations, are they? I say, because I have to know about altruistic psychology for an upcoming assessment, but I spend too much of my time procrastinating with pointless mobile games...

I've got an exam coming up on the 9th of January, and I've not really prepared for it at all yet. Thoughts have been getting in the way, about how poorly my university experience has gone, how I should just drop out since I don't have a future anyway. How the most important thing I've learned while here is that I'll forever be some social outcast, that I've never stopped being the kind of socially repellent weirdo who's picked last, reluctantly, for the team in PE, which I'm okay with since I don't like PE anyway but it still hurts to be so undesired. Uh, let's pretend that was a better metaphor for my life in general. I wonder whether I should just give it all up, become a hermit, find a little flat to live in alone for a year or so before my savings run out and I end my life. A Happy New Year it would surely be for me!

But since I'm here, I might as well at least try to do a bit of revision for this exam. It's actually about aspects of psychology that I'm interested in, and which I think about anyway, but when we

have to do something, it seems to be so much easier to procrastinate than to actually do it. Frustrating, that. It's like any desire or interest is sapped away and replaced by fearful reluctance, for me at least. I get anxious at the thought of even opening the online lecture slides to make notes.

But I was thinking about something I want to write a post here about - as I often do - and I realised that it actually ties into the lecture I intended to make notes about today, to some degree. So I thought what I might try to do is, rather than just taking dry, semi-mindless notes from what's been provided to me, I'll try to write a post about what's on my mind, incorporating the lecture content so then I can better absorb it and so then I might feel more enjoyment and motivation about actually working through this revision. I do feel it's interesting material anyway, so maybe someone else would learn something from me writing about this too. Let's see how it goes.

![]()

It seems that most of the few games I play these days - apart from the recent VR ones - are mobile games. They're different from the games I grew up with in that rather than being something you start, spend a few days on, finish, then mostly forget about and move on, they aim to root themselves in your life, to become a daily routine. I don't mind that. I've been quite enjoying - to the extent that depression allows me to 'enjoy' anything - waking up to play a couple of them in the mornings before I get out of bed. It's a fairly nice thing to wake up to, and gives a kind of structure to my lonely mornings that I didn't really have before.

I've been playing one called

Futurama: Worlds of Tomorrow for months now, since its release; I talked about it in

∞ this post ∞ a couple of weeks ago. It's... tedious. I'm sticking with it mostly out of obligation, and because of linked memories; I got it just before I went to South Korea, and now when I play it I often think of how I played it while there. They're not even pleasant memories - largely I'm reminded of the pain of being rejected by someone I thought was my friend - but I suppose feeling

something is better than feeling nothing, so the thought of cutting this game out of my life feels wrong and undesirable.

But I wouldn't call it fun. It has these weeks-long events with limited time characters to acquire, and they typically involve doing agonisingly repetitive tasks to grind away resources in time, or waiting for like six hours for a

chance that some necessary item will drop from a tapped-on building, only to find out that, oh dear, it hasn't, so you have to wait yet another six hours as the event's clock continues to tick away. Unless of course you pay with premium currency... but I'll get to that shortly.

The frustration that comes from all this - and bafflement that the developers would consider the features good ideas - led me searching to see if other people felt similarly to me, or whether they actually enjoyed this sort of thing. I found this

∞ subreddit ∞, which I've been checking fairly regularly despite feeling that Reddit isn't really my kind of place (I haven't posted though, I just lurk). It seems that the prevailing attitude among the players is that the game is a grueling chore and that each new feature makes the game worse, each new event is the worst one ever. "I'm done with this game!" posts are common. It's darkly amusing actually how this game reminds me of my relationship with that friend because I played it when I knew her, and these posts remind me of it too by making me reflect on how I was dropped in the same way these people drop this game: we can only take so much frustration before it becomes unbearable, and it becomes a huge relief to just cut out the source of that frustration.

Anyway. Games like this are free-to-play... which means that the developers have to make money somehow. They do so by selling a premium currency, as is typical, and they make tasks tedious or difficult in order to encourage people to spend real money on that premium currency. But - as has come up many times in that subreddit - if people feel

coerced into something they don't really want to do but feel they

have to do just to avoid negative consequences, then that's going to cultivate a bitter attitude towards the thing rather than making them want to come back for more (again, I think of that failed friendship... but everything reminds me of that these days). It ideally

should be that you can spend money on things that are extra bonuses, if you want to, once you've been hooked by the actually enjoyable free content. You'd be paying money out of respect and love and you'd probably stick around longer because of that. But of course ideals and reality rarely line up.

It seems that the way these kinds of mobile games often go about adding peripheral paid content is in the form of what's essentially a gamble. Loot boxes; the term 'gacha' (from

∞ gachapon ∞) seems to be used for the games as a genre, considering the Eastern origins of such mechanics. Rather than simply having a character on sale for a certain price, instead you pay for the

chance - usually a slim chance - of getting either that character, or what's essentially junk. It seems like an awful system to me, but I imagine it's very profitable because of how psychology works; intermittent reinforcement schedules, where you get a reward only sometimes, evoke more behaviours than schedules where a reward is guaranteed.

I've recently started playing a game called

Star Wars: Galaxy of Heroes (I think that's its title??), despite having little to no interest in Star Wars. I got it because it was advertised in that Futurama game (I suppose adverts work sometimes), because one of my housemates is obsessed with

∞ Star Wars Rebels ∞, and also because it looked like it had JRPG-style turn-based battles, which surprised me and piqued my curiosity. I'm quite impressed by it, despite all the trappings of these tedious, money-sucking, grind-heavy gacha games. Maybe it's just because I'm using the Futurama game's bare-bones combat system as a direct comparison, but I like how the battles in this are simple but actually incorporate some kind of strategy. Or at least the feeling of strategy. I also find the graphics and animations satisfying in themselves.

![]()

Though I've never spent a penny on what I'll annoyingly call F:WoT since day one, I spent £4.99 on this Star Wars thing on my second day of playing... after much reluctant deliberation, eventually reasoning that I'll probably be dead soon anyway so why not just spend a little bit of money on some entertainment while I can (because I have healthy thought processes, you see). I paid to unlock a character, Count Dooku, and for the most part I've been quite happy with that purchase. I use that character all the time, and he has abilities that are inherently satisfying, like being able to attack twice and counterattack whenever he's hit. I don't regret buying him, especially since I've stuck with the game since then, the investment wasn't high (I also got a bunch of resources and things from the starter pack I bought with him in), and I knew what I was getting. It's probably encouraged me to stick with the game, actually, now that I've become monetarily invested.

![]()

But. Characters in this game are acquired or 'promoted' by collecting 'shards', as seems to be common in this genre. So one mission (which is always just three consecutive battles) might give a chance of rewarding you with a single shard for a character, and you need 25 to unlock them, say, or maybe 25 more to promote them from three stars to four, boosting their power. Much of my daily play time, then, is spent grinding missions in order to collect shards so then I can unlock or promote some characters I have my eye on (though thankfully it has this really nice feature where you can spend a 'sim ticket' to instantly get the rewards for a mission without having to actually trudge through any battles, and you can also easily track down exactly which missions you need to do to get whatever item or shard you're looking for). Characters come in factions, and tend to have synergy with one other characters from the same faction. I've been aiming to collect characters from the faction from Star Wars Rebels, which I've never personally seen, but my flatmate talks about it enough that I feel some sense of familiarity with them, and it seems they become quite a potent party if you have five of them working together as a group.

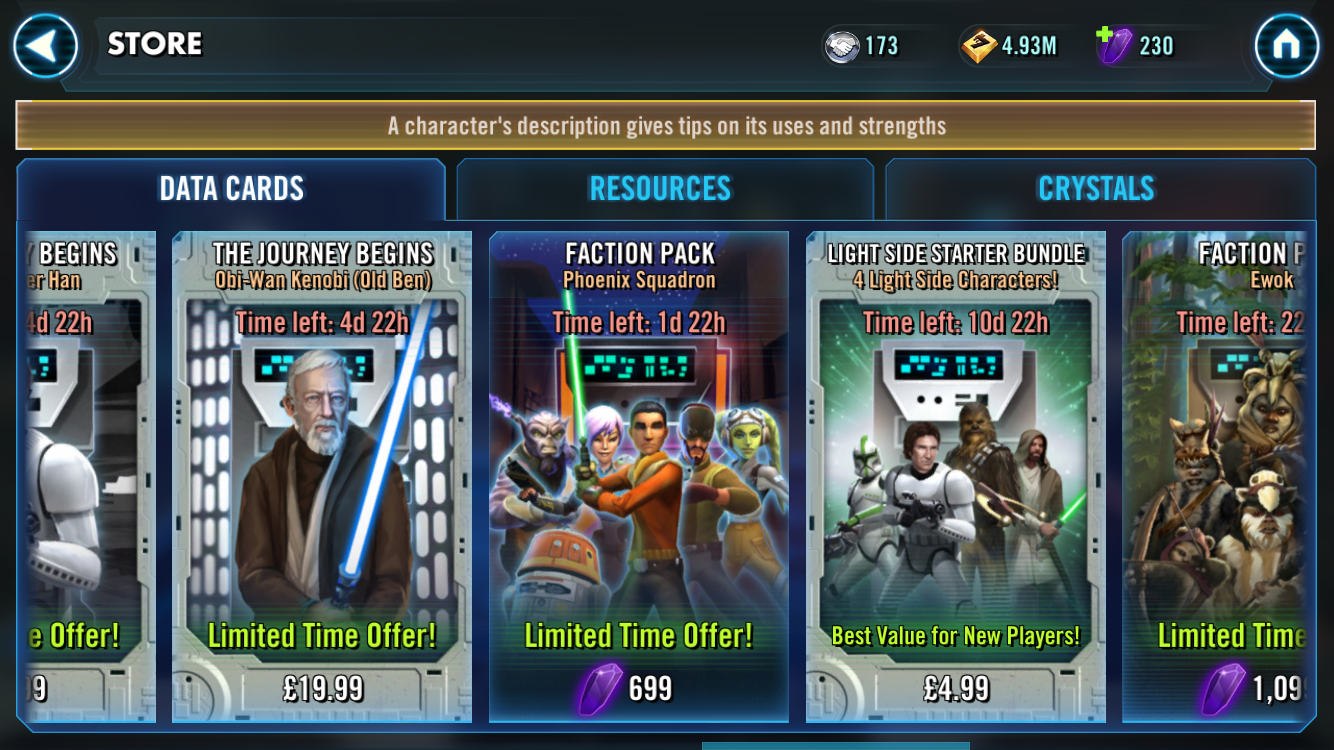

There's a shop, of course, which looks like this:

![]()

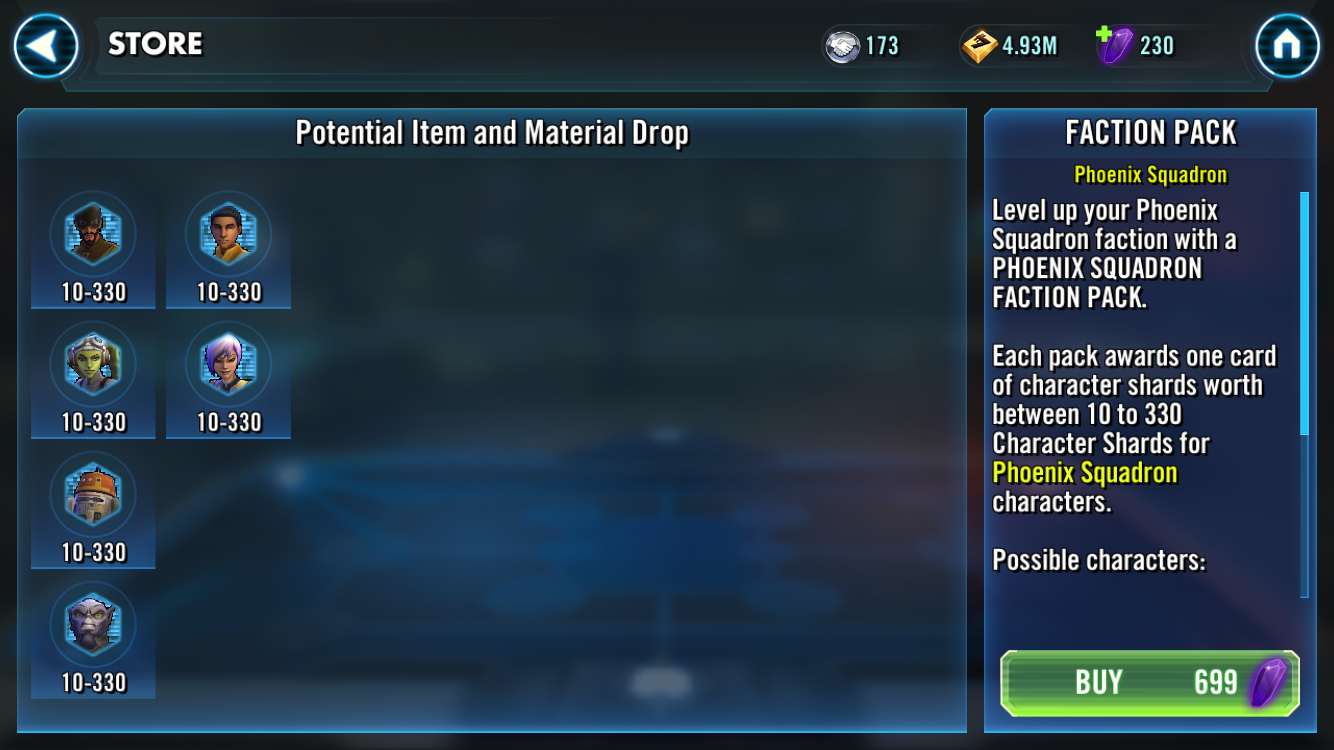

Today, I noticed that there was that limited-time offer for characters from this set that I'm collecting (the Phoenix Squadron), so I thought ooh, I actually want that (unlike with all the other overpriced stuff which I feel annoyed just looking at; £20 for a single character??). This was the offer:

![]()

It seemed... unfair, since you only get shards for a single random character, and you get a random amount of them, too. So nothing is guaranteed. These characters take around 25 shards to promote or unlock, so while there was a chance I'd get shards for a character I already had instead of unlocking a new one, I was tempted by the thought of getting as many as 330 shards and being able to promote one probably all the way up to eight stars, maybe. That would be so powerful!!!!1!1 I naively assumed that the amount range was linear, so I'd get about 170 shards on average (ridiculously foolish of me in hindsight). So I thought okay, since I'm trying to collect these characters using tedious grinding anyway (and I'll be dead soon, of course), I

may as well take this opportunity since it might have a very satisfying payoff. It might be worth the money.

So I spent £9.99 on a bunch of premium currency, enough to buy this thing twice. I thought that even if I got a poor haul the first time, at least a second go might give me better odds of getting something I'd be happy with.

But, surely to the surprise of nobody, I didn't get something I was happy with. For my first purchase, I got 10 shards for a character I already had. Okay, I thought. Just bad luck. I can try again. So I did... and got 12 shards for

the same character, which just made me glare bitterly at the screen for quite a while.

It made me question how wise this kind of strategy is if it has the potential to completely sour a player's opinion of the game as a whole. It certainly made me never want to pay for one of these """deals""" again, since I felt I'd just thrown away an amount of money that's non-trivial for me, without anything to really show for it. Technically I was able to promote that one character, but getting only 22 shards when I could have got 660 invalidated any appreciation I might have had for that. When we know what we

could have, we feel worse about what we do have if it can't compare.

(Apparently it is - or will become - legally required to show the odds for these loot box things so you know the chances of each of the outcomes. I imagine something like this would have chances like 50% for 10 shards, a further 30% for 12, and an infinitesimal chance of 330 just so they can technically say that's a possibility even though practically it isn't... and if I'd have known that at the start, I wouldn't have paid at all. Now I just feel worse about being deceived, though. Thanks, game.)

I'm probably going to remember that every time I play the game now, and I'll feel worse about it than I did before. I imagine there are a few people who do pay a lot of money on these what-are-essentially-slot-machines, hoping to score big (apparently they're called 'whales', originating from

∞ a term used in casinos ∞), and those are the ones the developers aim to appeal to, to bleed dry. But then the majority of players, who aren't that way inclined, end up having their experience effectively ruined as a result. But I suppose that's the way the whole world works... The misery of many to maintain the pleasure of a few. Or something.

Wouldn't it be nicer if the purchases were actually pleasurable instead? Wouldn't that encourage people to buy more? Perhaps not. Perhaps most people are reluctant to pay anything at all, and those who are willing to pay

something are probably not going to be put off by the unsatisfying results of that decision. Perhaps. I don't know; I imagine a lot's been written about the psychology of this.

It's interesting that despite there being like a billion characters you can technically acquire in this game (I counted them and there are literally a billion), pretty much all the groups I go up against in the sort-of PvP (computer-controlled players' parties) have the same selection of free characters given out right at the start (so my strategy is pretty much always to take out their Talia, remove their Chewbacca's taunt, then get rid of their Jedi Consular, their Kylo Ren, their Farmboy Luke Skywalker, then finally their Chewbacca; I'm sure you were dying to know this) . People who pay for characters must be a tiny minority, but I suppose it's always that way. The whole business model for these free-to-play games seems doomed to create misery for everyone, really.

But this overly-long preamble

finally leads me onto psychology stuff, about altruism...

![]()

Altruism is a strange thing, in that it doesn't really make much sense from a evolutionary, survival perspective for an individual to sacrifice their own needs or wellbeing (or 'fitness', as it seems to be called) for the benefit of another. To pay a cost so that another might gain. If we exist to breed - and we do - then why would we save Grandma from her burning bungalow - putting our own life on the line to save hers - if we've not even produced any children yet? If we tripped over an errant doily and perished in the cat-pee-smelling conflagration, our genes' journey comes to an end. They don't want that, generally speaking.

But what even

are genes? We're all familiar with the term, I imagine, but I didn't actually understand fully what it referred to in a biological sense until I started reading

The Selfish Gene, by

∞ that delightful chap Richard Dawkins ∞, who I used to look up to quite a bit. Ah, those were the days. I have to read this book for this module, but I've only read the first couple of chapters. I don't think I'm going to be able to read the whole thing in the next, what, week? On top of everything else. Annoying, that. If only I'd started sooner. If only.

Anyway, what I did read was quite enlightening in terms of what genes actually

are (other than selfish, as a brisk perusal of the title would elucidate). As you may know, our DNA is made up of helix-stringed pairs of four nucleotides: adenine, cytosine, thymine, and guanine. Their order is the 'code' which determines how creatures turn out. A 'gene' is a segment of DNA; I suppose you could say each nucleotide (or pair of them) is a letter, and a gene is a word made up of several of these letters. Then you have chromosomes, which are made of multiple genes; a sentence, if you like. Or I suppose Dawkins described it better by saying that each gene is a page of a book, and a chromosome is a whole volume of these pages; that gives a better idea of the scale of things like genes and chromosomes, which have an awful lot of nucleotides in them in order to bring about such complexity.

When a man and a woman love each other very much, and he gruntingly thrusts his engorged man-sausage into her slimy lady-hole and shoots a barrage of titchy tadpoles, one of which successfully penetrates her egg much as its daddy did to her... ham sandwich (I'm hungry), a transfer of genes occurs to produce a child that shares roughly 50% of its genes with each of its parents. But the genes you get from each parent are random, otherwise all siblings would be the same (how this works is more complicated than I can be bothered to understand, especially since I don't need to, though it bothers me a bit that I don't have the time or energy to look into it). Each gene fills a 'slot', but they come in variations; for example, the eye colour gene comes in blue, brown, green, etc versions. These gene variations - called alleles - effectively compete for the same position on the chromosome; they're 'rivals'.

Genes very likely evolved from ancient, ancient reproducing molecules, way back when the distinction between animate and inanimate matter was just starting to happen. If some lifeless particles were able to somehow duplicate themselves (who knows how), they'd eventually spread. The duplication would likely be imperfect - because reality is - but some errors introduced would allow the molecule to reproduce more - or less - successfully. Over time, these adaptations - passed, of course, to the next generation through the duplication process - would build up, and complexity would form. Molecules that developed the ability to steal resources off other molecules - to feed on them - would speed up their own ability to reproduce, and inter-'species' conflict would develop. Over many billions of years, this would lead to platypuses, elephants, humans, ham sandwiches, muskrats, and so on.

But Dawkins talks about complex bodies as being essentially just big, lumbering, temporary machines that these simple replicating molecules have built for themselves in order to facilitate their reproduction. The genes are effectively immortal, as they have copies passed to the next generation, but individuals aren't copied (as such) to the next generation; they're very much ephemeral by comparison. Like a tremendous burst of flatulence ripped forth to propel oneself across a gully. We are that flatulence. Evolution is all about 'survival of the fittest' (to put it simply), but the selection of who's 'fit' or not doesn't happen on the level of the individual organisms. It happens on the level of the genes.

Genes can cooperate with one another, in the sense that 'teaming up' in a chromosome allows them to build more complex bodies than they could by themselves. However, they're also in competition with alleles who want to take their spot on that chromosome. It's like the chromosome is a huge canoe and the genes are sprightly young men, toned muscles glistening in the sun, each wrestling other lithe and frisky young men in order to win their position pumping away at the 902nd oar on the left. And oh how they pump! In out, round and round. Like a ripped piston. Oh my. So yes, that's exactly what alleles are. Wrestling young men. Sweaty, wrestling young men. They're only wearing speedos, you know. Our alleles. Because they're just so hot. Meow.

Altruism! That's what I'm talking about. Or I'm getting to it, anyway. It might seem 'obvious' that social animals would behave altruistically 'for the good of the species', but this doesn't really mean anything as far as the genes are concerned. Dave the muskrat and Sally the muskrat might have completely different family trees and very few genes in common (well, apart from the overwhelming majority of shared genes that make them both muskrats, but apparently all this stuff deals with the genes that

aren't shared between individuals of a species), so why should she risk her life to screech out to him when she spots an eagle swooping in for the kill? She isn't concerned about muskrat kind (it's at this point I look up what a muskrat even is... oh, I see, fascinating, how interesting); she probably wouldn't even be aware that there is a wider species of 'her kind', really. Why, how would the genes know that? She already loves her dear muskrat husband, also confusingly called Dave, and if anything she finds Dave - this one, not her husband - obnoxious, what with his incessant, sleazy offers to let her get her hands on his nuts. Do muskrats eat nuts? They live in ponds, Wikipedia says, so probably not. So why should she care about him enough to save him? Why be altruistic?

Well. Genes' aim is to survive, and this can be done most clearly through squeezing out babies; this is called direct fitness, since the genes are spreading themselves directly to the next generation. However, it's also true individuals share genes with their family, their kin, so lending your sister a thousand pounds to pay off the goons who are threatening to smash her shins would help spread the blue eye genes you share with her to the next generation via all the frisky moaning she does with that arsehole Greg she's somehow become enamoured with. He's the one who got her into gambling in the first place, and he has such an annoying laugh. Ugh. By helping her, you are in a sense saving a part of yourself; the only part that matters as far as your genes are concerned. Direct and this indirect fitness together are called inclusive fitness, because everyone loves memorising jargon. Also, acting more altruistically towards family is called kin selection, for bonus jargon points.

But it's not really worth it if the cost for you is greater than the benefit for her. It's not like you're going to chop off your own legs for those goons to spare her the fate of shattered shins. There's this thing called Hamilton's Law - thought up by a guy called... Axelrod, obviously - which puts it into formula form: altruism would probably happen if B x r > C, where B is the benefit to the other, C is the cost to you, and r is something called the coefficient of relatedness, which is essentially the ratio of genes you share with that other. For siblings and parents, r = 0.5, because you share 50% of your genes with each of them, roughly speaking. For your dear old grandmother, burning in that fire because she insists on living alone despite being as blind as she is senile, r = 0.25, because she shares half of her genes with one of your parents, so a quarter with you. So you'd save her only if you'd only lose less than 25% of your HP by rushing into the inferno. (Though she's reproductively barren, so that seems to have an influence too; saving her won't help your genes spread because it's not like she's going to be having any more offspring now that poor Barney is playing pool with angels in Heaven. He did love pool, you know. That and she's post-menopausal, so she's not going to be plopping out any little ploppers no matter how many times that creepy delivery boy hits her up. I hope you're picturing all this vividly.)

You can't just come up with some random law in science and claim it to be true, to be awarded the Science Crown and be given a Science Throne to sit upon for the rest of time. You have to actually demonstrate its accuracy in experiments, and there don't seem to be many assessing Hamilton's Law. Most of them have just been questionnaires; people were asked who they'd help in certain situations, or something like "how likely would you be to help your step-aunt fight a rampaging bull?". And it does turn out that people are more likely to help their relatives, and they're more likely to help out their closer relatives (parents, siblings) when the risk is greater. I think they're also more likely to help out female relatives, interestingly? I assume that's cultural as much as anything though, with it being seen as noble to help out a poor, vulnerable lady but not so much a poor, vulnerable man.

There was also an interesting experiment where people had to stand in some painful, awkward pose with their back against a wall and their bum hovering above a laser beam; when they inevitably failed and fell to the cold, hard floor, shattering their sacrum for the sake of science, their fat arse triggered the beam and ended the trial. They were asked to endure as long as they could, with money being paid the longer they lasted; something paltry like £1.50 a minute, paid either to the participant directly, their mother, their uncle, or charity (or something like that). Shockingly, people lasted longest when

they were getting the money, but they also seemed to last longer the closer the other person was to them. I wonder though whether that's because they could reap the direct benefits if it happened to be someone they lived with, hmm.

Also, delightfully, step-parents are much more likely to murder their step-children than biological parents are to murder their biological children. I hope that's a fact you'll succinctly share at the many cocktail parties everyone but me goes to, followed by a pause and a toothy-grinned stare lingering for far too long.

You can also invert Hamilton's rule to get an idea of when the decision might be made to refrain from helping out one of your myriad loved ones. If your lovely brother is asking for £600,000 of that sweet, sweet one mill you recently stole from the local bank, then B > C / r (that is, the benefit is more than twice the cost to you; r = 0.5 here), and you're not likely to help out. Essentially, you'd only help out if your sibling's need was twice as great as your own. Otherwise intersibling rivalry would occur. This could more generally be classed under 'conflicts of genetic interest'; everything we'd do would be to maximise the survival chances of our own genes. So if parents feel that one of their children is a hopeless parasite who's draining their resources and will to live, and who'll never in a million years find a girlfriend living in that basement of theirs at the ripe old age of fifty, gods, then they're probably going to dump him in the woods and cut off all ties with him to focus all their attention to the little blighter his far-more-successful sister recently spawned into being.

It's definitely true though that we act altruistically even to people who aren't going to help out on our genes' immortal journey at all. This is usually reciprocal altruism, where you do something good for someone else expecting them to repay the favour in some form. You'd probably save a billionaire from being squashed like a pancake under a runaway bowling ball in the hope that he'll give you his entire fortune and his hand in marriage, but you'd probably just stand and watch a homeless man's eyes pop out of his sockets as that bowling ball burst his skull like an egg, hands shaking on your filming phone as you wriggled with sadistic glee. Everyone would! Everyone would do these things!! That's what psychology says, verbatim!!!

Well, it's not that simple, obviously. It's interesting though to think that in a society where some people are goody-two-shoes who help every old lady they see cross the street, and others are baddy-steals-shoes who happily get helped by these angels while contributing no help of their own, the latter are more likely to thrive because they're reaping all the benefits while paying none of the costs. This strategy would be better overall, and would lead to improved survival chances, so eventually all the selfish people would be having selfish children, and over generations all the altruists would die out, bitter and exhausted. You'd be left with a society full of selfish cheaters, who'd be much worse off than if they were helping one another.

Perhaps you could argue that humanity has already fallen victim to this survival strategy, but it's interesting to look at how people typically respond to something called the Prisoner's Dilemma and see that this isn't necessarily the case. If you're not familiar with the Prisoner's Dilemma, essentially you and your mate Dave have robbed a bank, as you do, and you find yourself in the interrogation room of a copper's hive, them having nabbed you, damn it. You and Dave are grilled separately, and both asked whether you're the ones who robbed the bank or not (they can't prove it's you otherwise). If you 'defect' and tell them it was all Dave's idea, but he doesn't do the same to you, you go free, and he gets ten years in a horrible muskrat jail, forever blocked from wooing Sally with his pilfered lucre. If he defects, but you don't, you get the ten years, he goes free. If you

both defect, you're both guilty, but you only get five years each. Better hope he's not better at swatting the muskrat soap out of your hands than you are out of his. If neither of you admit to your terrible crime, nor do you blame your colleague - that is, you cooperate - then you each get only a single year, because they can't prove nothin'. I'm sure that year would just fly by. 'Obviously' it's better to defect; if you defect and Dave doesn't, you get nothing and he gets Hell. If you cooperate, prison is guaranteed. So you'd expect most people to betray, right, especially considering what wretched, selfish things we humans are?

Or maybe you already know that no, most people choose to cooperate, despite the risks, and the guaranteed misery. This is odd, since it 'should' be that we'd evolve to be selfish cheaters, as that way we'd reap benefits from and pay no costs to those who do decide to be nice and help out. But we evolved to have

repeated interactions with other people, which throws a wrench in that kind of anti-altruistic strategy. A guy called Trivers suggested that reciprocal altruism develops in conditions where the benefit outweighs the cost, where the individuals are able to remember other individuals that they come across, and where they come across individuals repeatedly; a group of tribal primates, say, who spend much of their time with the same small group. If Dave the muskrat (the other one, Sally's charming husband) repays your lending him £100,000 of the million you stole (because he's such a swell guy) by forgetting about your birthday, then it'd be senseless to keep helping him out when he keeps coming back for another slice of your glittering coin pie. Yum yum. No, you'd remember him, change his category from 'swell guy' to 'just as bad as that other Dave who's rotting away in Muscatraz thanks to me', and refuse to altruise him again. This is a 'tit-for-tat' strategy, so named because people tend to show a bit of bosom in exchange for shoddy goods, but not if you don't give them anything. Or rather, it pays to start with cooperation, then to reciprocate whatever they do to you; a modified Golden Rule, "do unto them as they did unto you". It's one of two 'evolutionary stable strategies', or ESSeses, which are superior to other strategies and as such don't get outbred like the pure altruism strategy would. So it's interesting that we

could have had a population of defectors who'd never help anyone but themselves (the other ESS)... but instead we ended up with this kind of reciprocal altruism, which I suppose is what led to us being able to erect skyscrapers and others' peni through our lusty cam shows.

The prisoner's dilemma doesn't have to refer to an actual prisoner situation, of course. It applies to all kinds of things that we do in life. Recycling, for example; if nobody could be bothered with it but still wanted a cleaner environment, then obviously nothing would be achieved because nobody would be recycling. So people recycle anyway (or at least some people do), despite it being costly to them.

It's also notable that in experiments with the prisoner's dilemma, usually it'd be a one-shot thing with a stranger you'd never see again. But when they have iterated versions, where you play multiple rounds with the other person and learn to anticipate what they might do, people tend to end up cooperating with one another eventually. Society in a nutshell, perhaps.

There's another, similarish thing called the Ultimatum Game. Say the billionaire banker whose million you stole catches you with his own sweaty hands, and goes above the law by proposing a little game you and Dave can play with his sweaty pocket change. You're asked how much of the million you want to keep, and how many you want to share with Dave. You can split it any way that you like. You could give Dave all of it, or just give him a penny, or none. It's entirely up to you. But if Dave refuses the amount you're going to split by, then the billionaire will take it all away! Most people, when faced with this situation which is presented in this exact way in every single one of the experiments, honestly, would split about half-and-half, though they don't really

have to. After all, even if Dave would only be getting a penny, he'd be shooting himself in the foot out of spite if he refused it, because he'd be missing out on a free penny. Whatever he'd get from the lowball offer would be better than the nothing he'd get by refusing. Still, spite seems to play a big role, and the threat of it is a deterrent for selfish offers (probably moreso than the desire to be kind and generous). The ratio of the split differs across cultures though. How interesting.

![]()

I hope you're impressed by how seamlessly I was able to link my seriously-written revision notes about altruism with my experiences with gacha games. I know I am. It really went just as well as I hoped it would, that. Yes. But it's time for beddy-byes now so I'll just leave this as it is. In conclusion, Dave's not enjoying prison.

![]()

He can't play mobile games in there, you see. Hands're too little.

0